Who votes for whom, and why? How has the social structure of the electorates of the various political tendencies in France evolved between 1789 and 2022? On the basis of an unprecedented project of digitalizing electoral and socioeconomic records covering more than two centuries, this book offers a history of voting and inequality based on the French laboratory. All the data collected from the approximately 36,000 municipalities in France are available on this website, which includes hundreds of other interactive maps, graphs, and tables that readers can use to deepen and refine their own analyses and hypotheses.

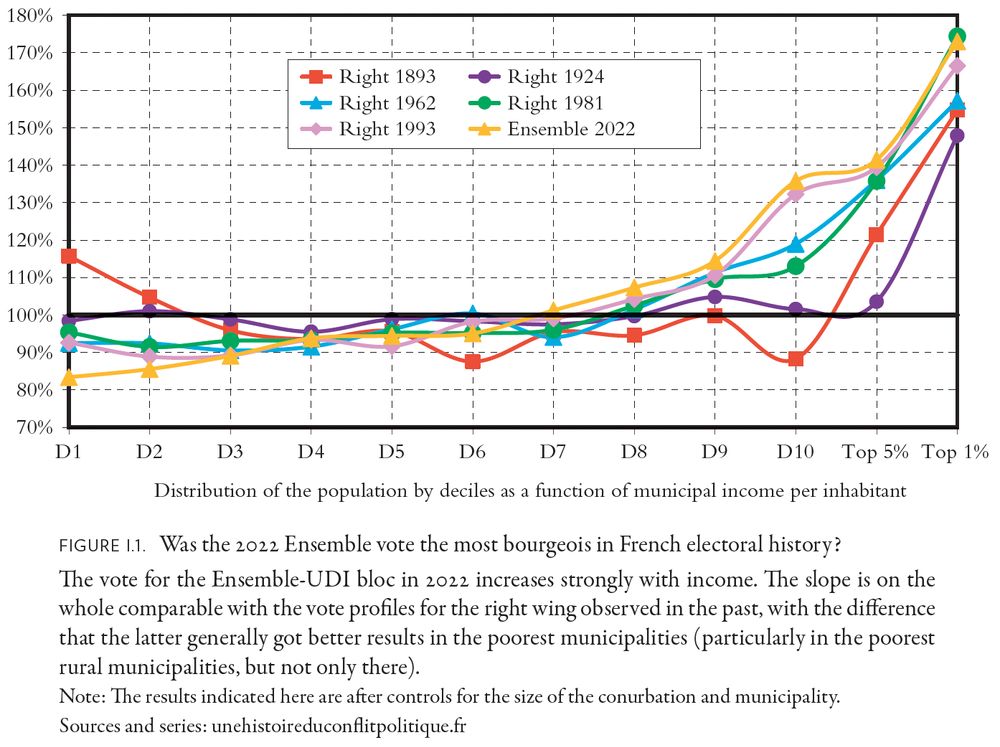

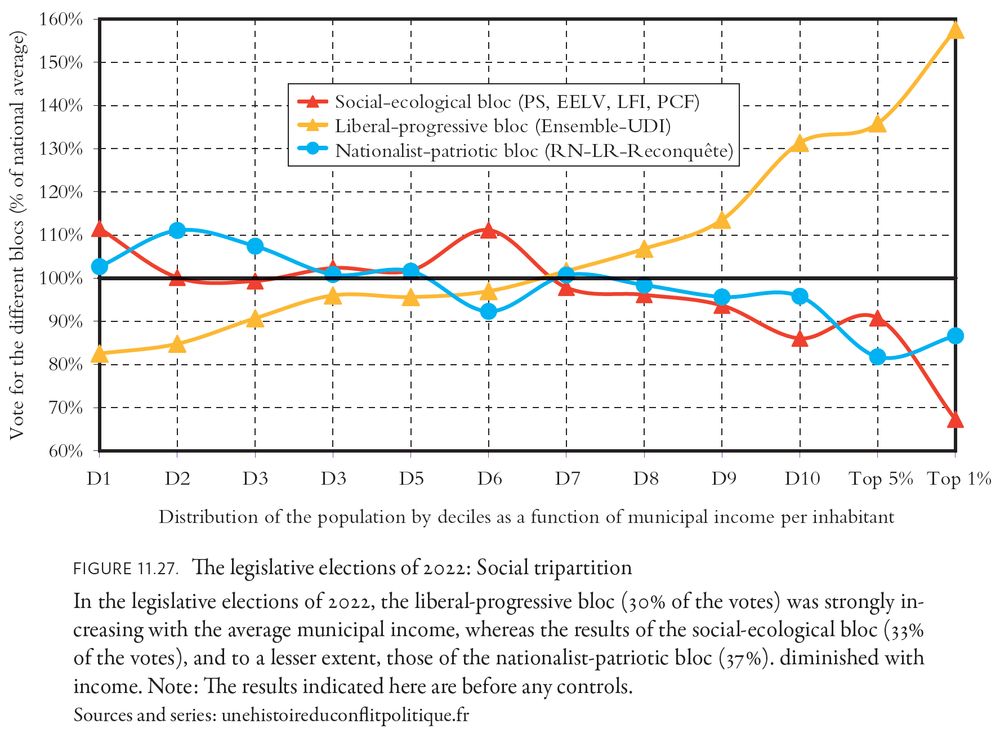

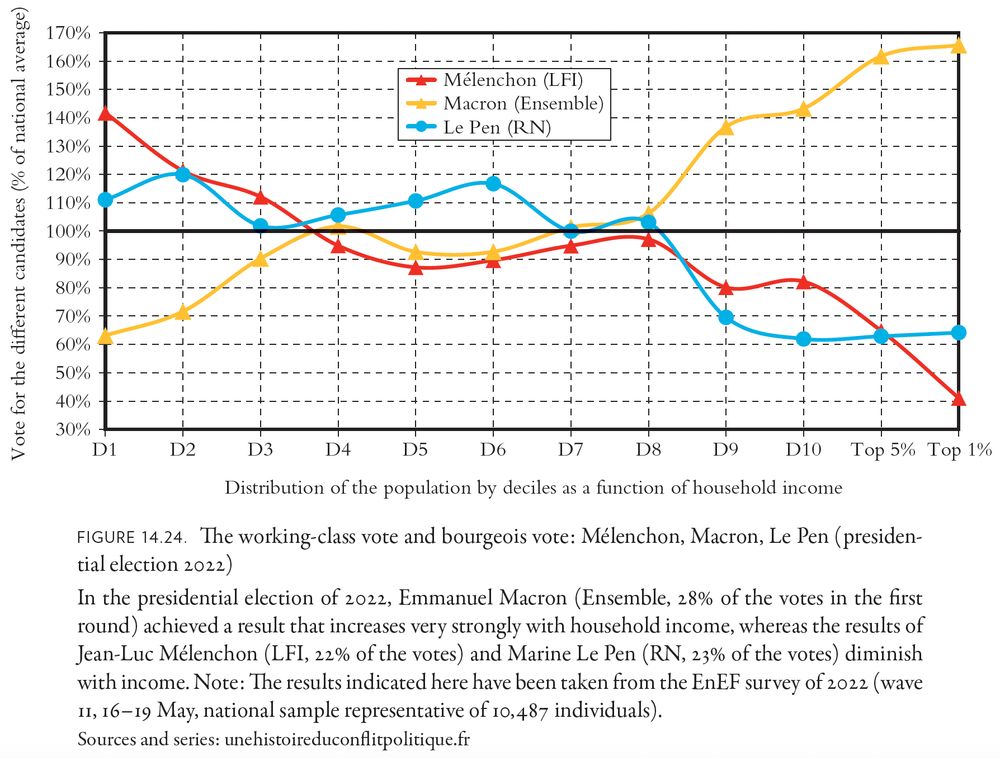

In addition to its historical interest and the new database that it provides, this work offers a new way of seeing the crises of the present and possible ways of resolving them. A historical perspective is needed to properly analyze the tripartition of political life that emerged from the 2022 elections, with, on the one hand, a central bloc comprising a much more socially privileged electorate than the average – and, according to the sources gathered here, representing the most bourgeois vote in French history – and, on the other hand, the urban and rural working classes divided between the other two blocs. In particular, it is only by going back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when similar forms of tripartition were observed before bipolarization prevailed for most of the last century, that we can understand the tensions at work today. Tripartition has always been unstable, whereas bipartition has enabled economic and social progress. A careful comparison of the different configurations provides a better understanding of several possible trajectories for the coming decades.

Introduction

Who votes for whom, and why? How did the social structure of the electorates of the various political tendencies in France evolve between 1789 and 2022? On the basis of an unprecedented project of digitalizing electoral and socioeconomic records covering more than two centuries, this book offers a history of voting and inequality based on the French laboratory. All the data collected from the approximately 36,000 municipalities in France are available on this website, which includes hundreds of other interactive maps, graphs, and tables that readers can use to deepen and refine their own analyses and hypotheses.

In addition to its historical interest and the new database that it provides, this work offers a new way of seeing the crises of the present and possible ways of resolving them. A historical perspective is needed to properly analyze the tripartition of political life that emerged from the 2022 elections, with, on the one hand, a central bloc comprising a much more socially privileged electorate than the average – and, according to the sources gathered here, representing the most bourgeois vote in French history – and, on the other hand, the urban and rural working classes divided between the other two blocs.

In particular, it is only by going back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when similar forms of tripartition were observed before bipolarization prevailed for most of the last century, that we can understand the tensions at work today. Tripartition has always been unstable, whereas bipartition has enabled economic and social progress. A careful comparison of the different configurations provides a better understanding of several possible trajectories for the coming decades.

Chapter 1 - A Limited and Tumultuous Advance toward Equality

Before studying the transformations of voting behaviors, in the first part of this book we analyze the main lines of the evolution of sociospatial inequalities in France since 1789. In Chapter 1 we first analyze what is probably the most striking structural development: a limited but real advance toward greater equality in France on the political, social, and economic levels since the Revolution, albeit with an interruption and the beginning of a new rise in inequalities in recent decades that today arouses profound concerns.

The movement toward political equality, however incomplete, has helped fuel a movement toward greater socioeconomic equality. Over the past two centuries, there has been a general rise in living standards, health, and education, as well as a significant reduction in income and wealth disparities over the long term.

This limited but real move towards greater equality and collective prosperity has been driven by popular mobilization. However, in France as in other European countries, the reduction in inequality cannot be attributed to a single political camp. Rather, it must be explored within the broader context of a political ecosystem characterized by a division between a social-democratic or socialist bloc and a Christian-democratic or conservative bloc (in the broad sense), with the two blocs alternating in power in a system of virtuous competition that has historically allowed for collective experimentation and the successful development of the welfare state.

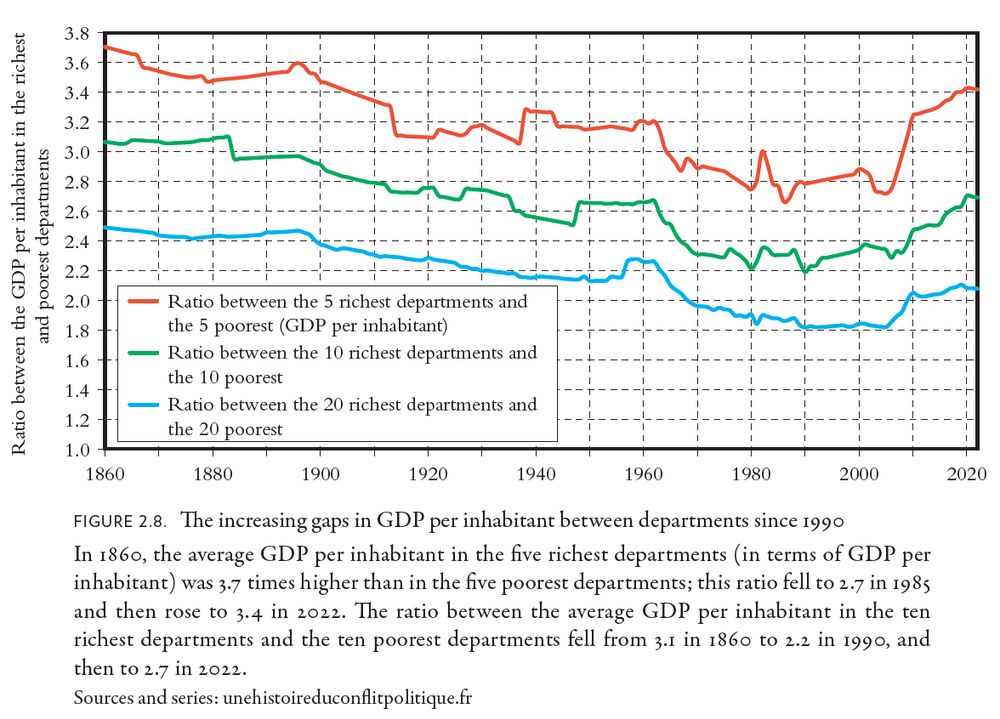

Chapter 2 - The Return of Territorial Inequalities

In Chapter 2 we study the main lines of the evolution of socioeconomic inequalities on the territorial and spatial level in France over a long period. We see that territorial inequalities, which had reduced significantly since the nineteenth century—though it is true that they were extremely high to start with—have begun to rise again since the 1980s–1990s. In the early 2020s, the differences in average GDP per capita between the richest and poorest departments thus returned to levels close to those observed between 1860 and 1900.

At the municipal level, there has also been a significant increase since the 1980s and 1990s in the gap between average real estate capital (value of housing) and average income between the poorest and richest municipalities. This trend can be seen in both rural and urban areas, in villages (defined here as conurbations with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants), towns (conurbations with between 2,000 and 100,000 inhabitants), suburbs (secondary municipalities in conurbations with more than 100,000 inhabitants) and metropoles (main municipalities in conurbations with more than 100,000 inhabitants).

The gap between poor and rich suburbs (the poorest 50% and the richest 50%) has widened significantly in recent decades, to the point that poor suburbs have fallen to the same level as poor villages and towns, or even below if we look at the poorest 20% or take into account inequalities in property prices and access to home ownership. There are also significant differences in terms of productive specialization: more service workers (commerce, catering, healthcare, etc.) in poor suburbs, more workers exposed to international competition in poor villages and towns, which was not the case before 1980-1990. This general framework—marked by the increasing complexity of class structure—provides an essential lens through which to analyze changes in voting behavior.

Chapter 3 - The Metamorphoses of Educational Inequalities

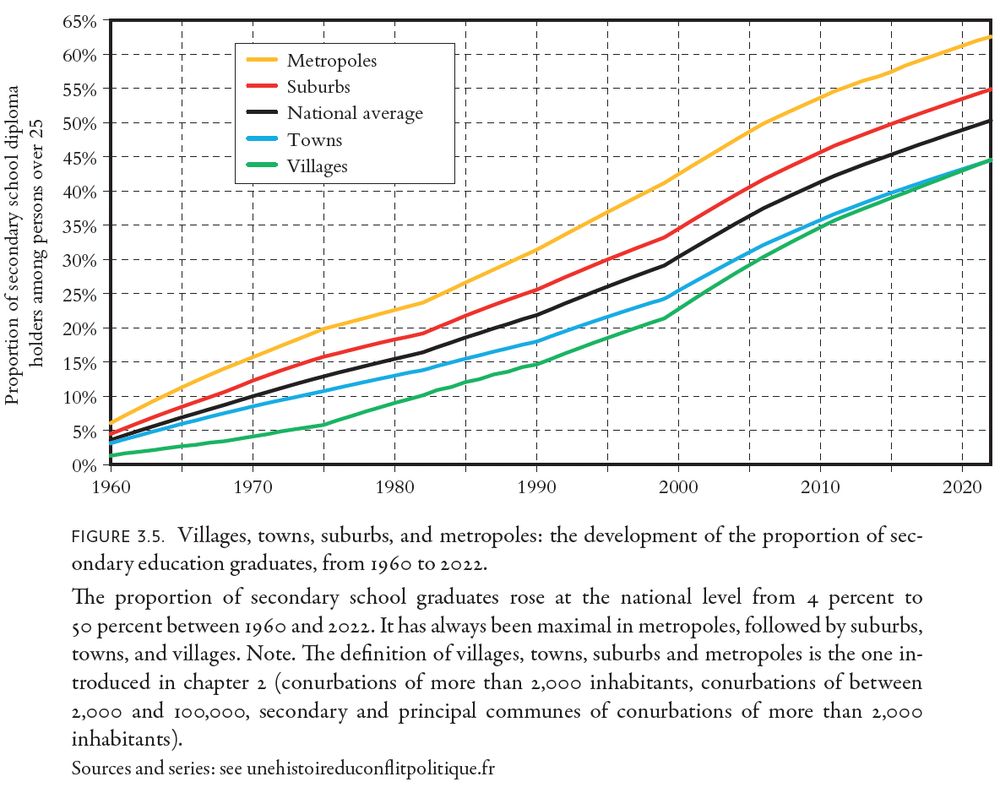

Chapter 3 focuses on educational inequalities and their metamorphoses. The major phenomenon over the long term is the persistence of very strong sociospatial inequalities in education in a context of an unprecedented expansion of the general level of access to knowledge and written culture over the past three centuries. These socioterritorial disparities partly intersect with those connected with production, real estate capital (total value of housing), and income, without, however, merging entirely with them. The proportion of secondary school graduates among the population aged 25 and over rose from 4% to 50% between 1960 and 2022 (and the proportion of higher education graduates rose from 2% to 34%), with a significantly higher increase in metropolises and suburbs than in towns and villages, linked to more accessible educational and university facilities in urban and rural areas.

It should be noted, however, that the education gap between poor suburbs and poor towns and villages is ultimately relatively small compared with the gap between these disadvantaged areas and the wealthiest suburbs and metropoles. As with income and wealth inequalities, disparities in educational inequalities are primarily found within each category of territory and size of conurbation. Educational inequalities are also exacerbated by the growing use of private education in the most advantaged areas, particularly in the most affluent metropolises and suburbs.

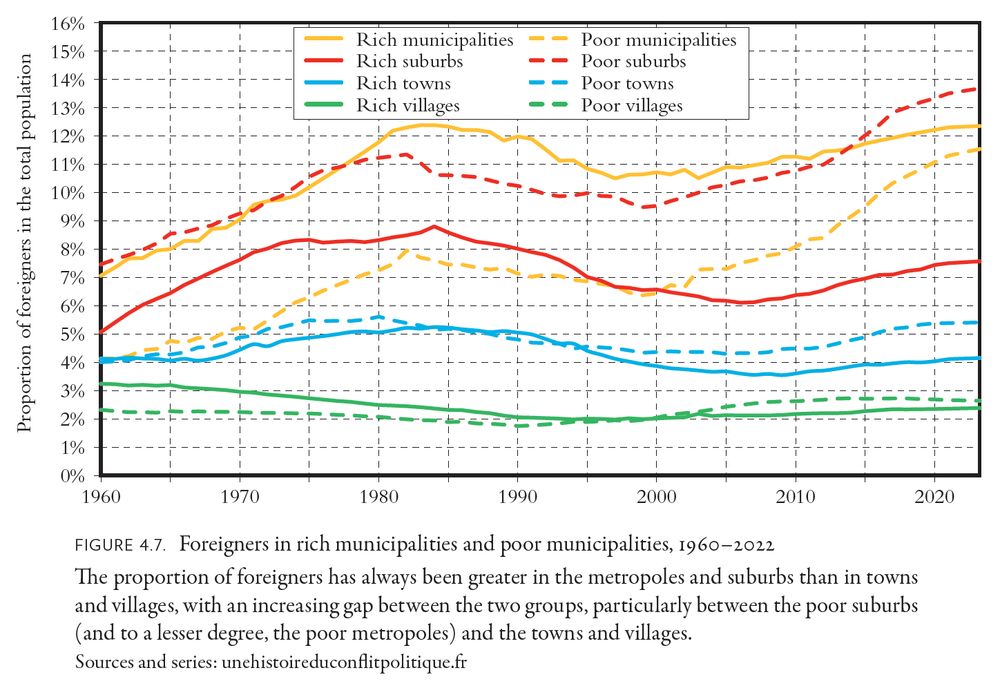

Chapter 4 - The New Diversity of Origins

We turn now to the new diversity of origins observed in Metropolitan France in recent decades. Since 1960–1970 we have seen the development of non-European immigration on a scale that can certainly be considered relatively modest in absolute terms, but which nonetheless constitutes a significant change with respect to earlier periods. At the time of the 1851 census, there were very few persons of foreign nationality in France: scarcely 1.1 percent of the total population. The proportion of foreigners (all nationalities combined) within the metropolitan population underwent irregular growth from the end of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, with a first peak in the interwar period (6.6% in 1931) and a second peak in the present period (7.4% in 2022). The increase observed since the post-war period, from 4.6% in 1960 to 7.4% in 2022, is significantly higher in urban areas, particularly in poor suburbs, than in towns and villages.

However, the findings presented in this chapter and throughout the book show that the differences between poor suburbs and poor villages and towns in terms of their experience of diversity and new forms of social interaction and mixed origins should not be exaggerated. Their scale is limited in comparison with everything that is common to all poor areas in urban and rural areas, particularly in terms of average income and access to public services, and also everything that differentiates them in socioeconomic terms, for example in terms of socio-professional structure (service employees vs. blue-collar workers) and the proportion of homeowners or higher education graduates.

Chapter 5 - The General Evolution of Turnout since 1789

The next three parts of the book take a closer look at electoral behaviors, focusing first on participation (Part 2), then on votes for the various political tendencies in legislative elections (Part 3), and finally on presidential and referenda votes (Part 4).

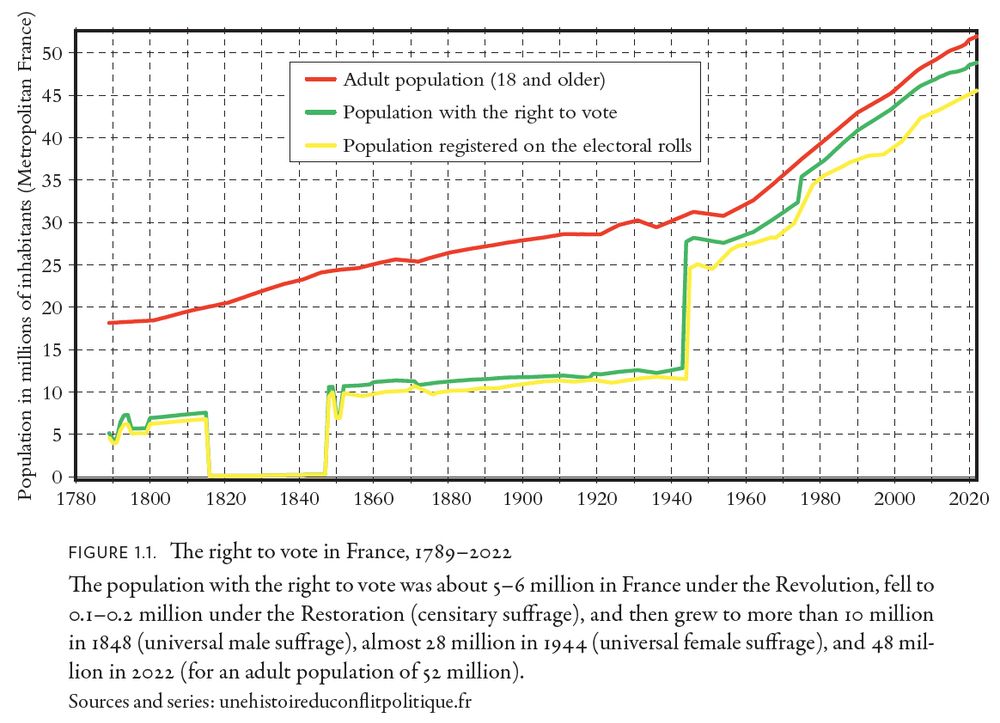

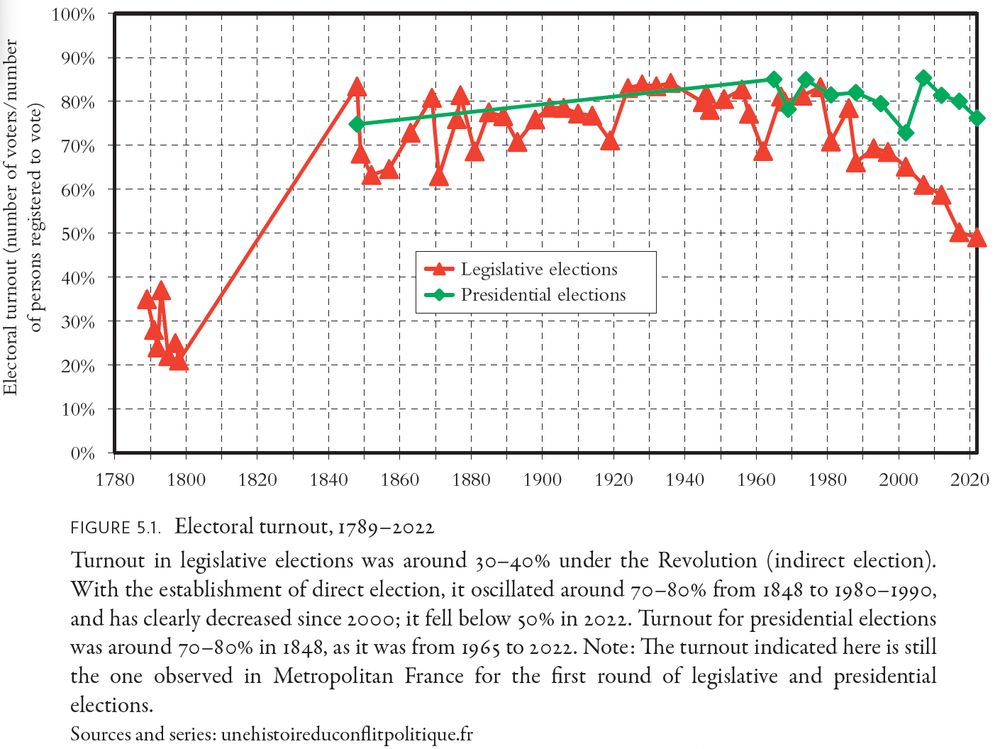

If we examine voting behaviors over the long term, one of the most striking facts is the boom in electoral turnout in the nineteenth century, its continuation at a high level during the second half of the nineteenth century and most of the twentieth, and then the rapid decline in turnout at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first. Specifically, the rate of turnout in national elections reached about 30 to 40 percent under the Revolution before rising to around 70 to 80 percent in 1848–1849 and stabilizing at that level until 1980–1990, and then undergoing a marked decline since 1990–2000, with less than 50 percent turnout among voters registered during the legislative elections of 2022 - the lowest level registered for two centuries.

It can also be seen that the voter registration rate remained at around 90% throughout the period 1848-2022, with no clear long-term trend. This implies that voter turnout, as usually measured, tends to overestimate actual turnout by about 10%. Since the nineteenth century, the average voter registration rate measured at the national level has always been significantly higher in villages and towns than in suburbs and metropoles. Since 1990-2000, there has also been a higher registration rate in wealthy municipalities than in poor municipalities, regardless of the size of the conurbation, a social cleavage that did not exist previously.

Chapter 6 - The Social Determinants of Voter Turnout in Legislative Elections, 1848–2022

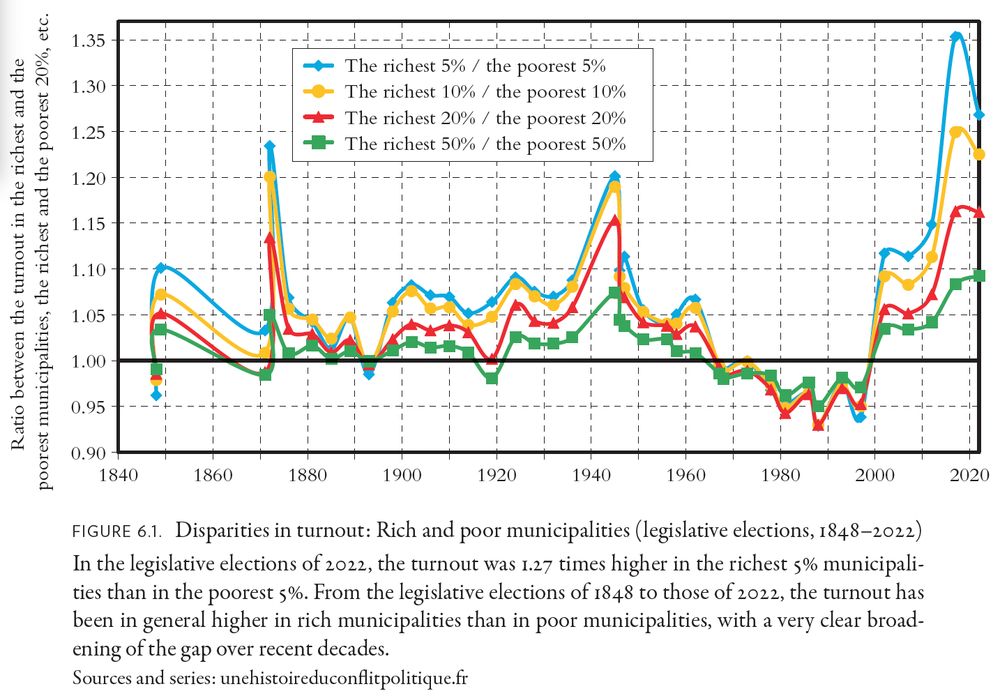

This chapter studies the structure of voter turnout and its transformations, from the legislative elections of 1848 to those of 2022. How do we explain that the turnout for legislative elections, which oscillated around 70–80 percent from 1848 to the 1980s and 1990s, fell so abruptly over the intervening decades and ended up at only 50 percent in 2017 and 2022?

We will see that this fall, far from being uniform, was accompanied by a growing disparity in turnout between rich and poor municipalities, to the extent that by the end of the 2010s and the beginning of the 2020s the size of the gap was unprecedented. We will also see that voter turnout has usually been greater in the rural world than in the urban world, from the legislative elections of 1848 to those of 2022, though with an important exception between 1920 and 1970 (particularly between 1930 and 1960) in connection with a strong working-class mobilization supporting the Communist Party.

Contrary to a received idea, the gap between rich and poor municipalities has not always existed, or at least it has not been so dramatic; it is essentially a recent evolution, unprecedented on the scale of French electoral history. The most convincing explanation, in our view, is the feeling of abandonment among the working classes since the 1980s and 1990s, linked to the weakening of the Left-Right divide. This feeling is closely linked to the perception that the economic programs of the main political parties are converging.

Chapter 7 - Turnout for Presidential Elections and Referenda, 1793-2022

This chapter studies the structure of voter turnout in presidential elections held in 1848 and from 1965 to 2022, as well as in referenda held since the constitutional referenda of 1793 and 1795 up to the European referenda of 1992 and 2005.

Generally speaking, we note for the presidential and legislative elections a growing disparity in turnout between rich and poor municipalities since the period 1980-1990, although the gap widened less significantly in the presidential elections and the overall turnout fell less sharply.

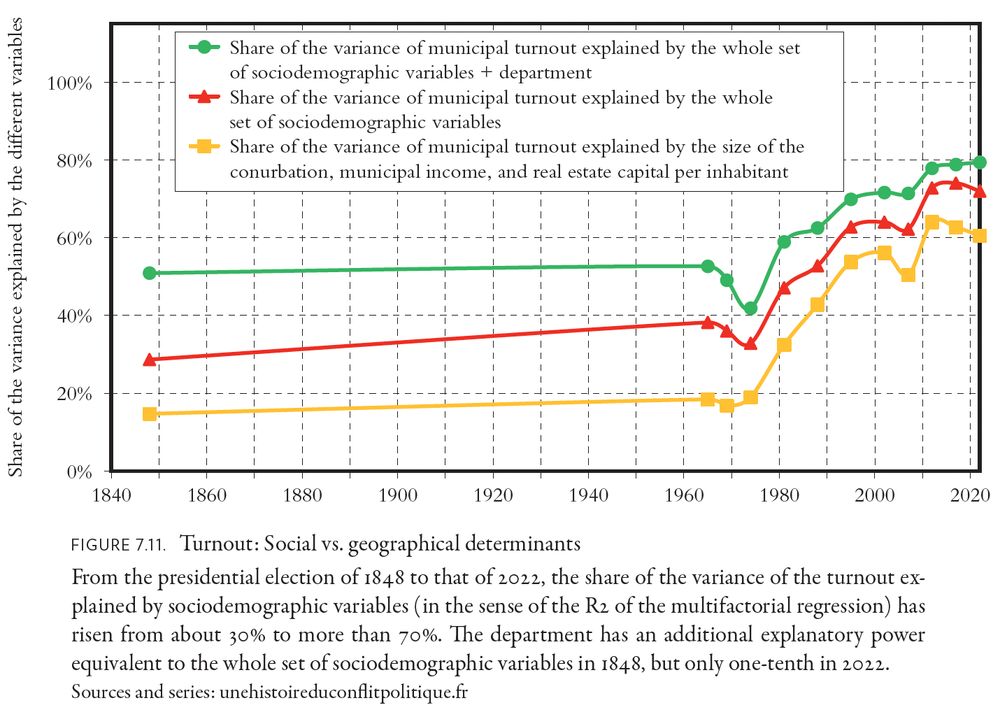

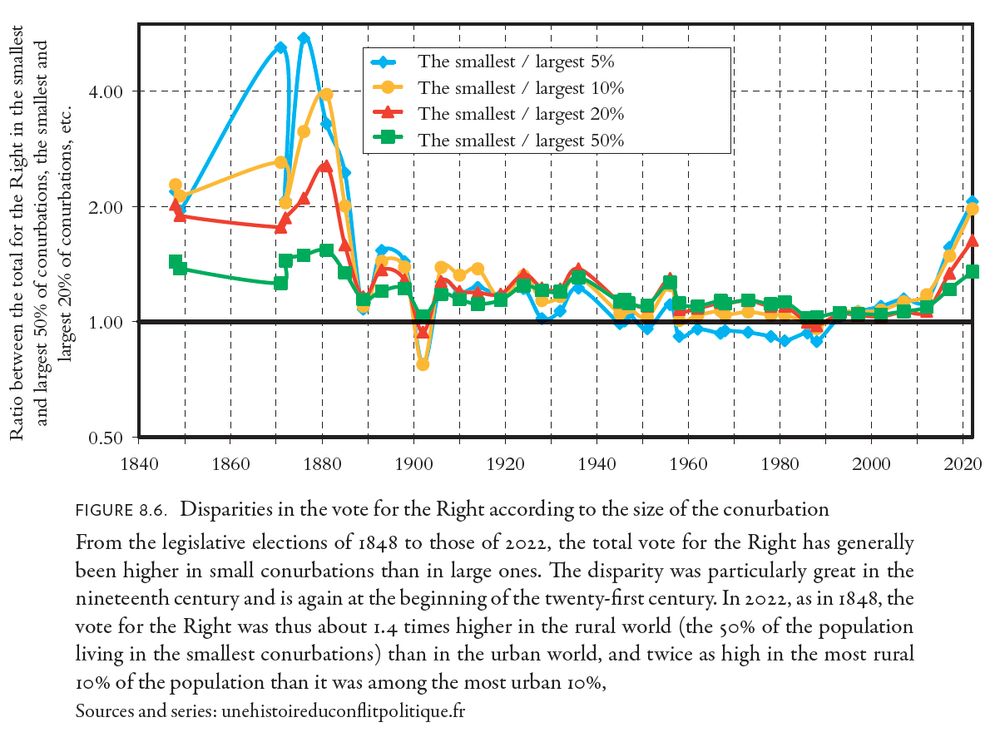

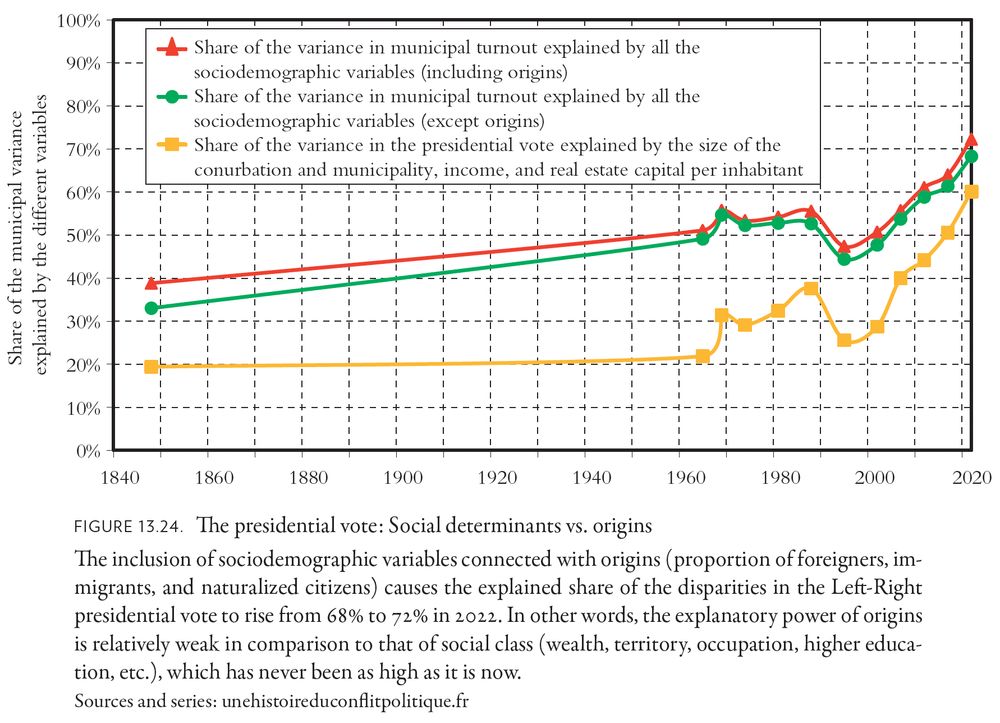

Over the long term, from 1848 to 2022, there was a sharp increase in the weight of social determinants of turnout, both in presidential and legislative elections. The main determinants of turnout are linked to geo-social class, with the wealth of the municipality (real estate capital, income, proportion of homeowners, concentration of land ownership) on the one hand, and the type of territory (size of conurbation and municipality: villages, towns, suburbs, metropoles) on the other. Other sociodemographic variables (occupation, sector of activity, level of education, etc.) also play a significant additional role. Variables related to religious practice or foreign origins have only a relatively limited impact. Finally, the additional explanatory power provided by the department has declined significantly over a long period.

Chapter 8 - Coalitions and Political Families, 1848-2022

This chapter presents the main outlines of the evolution of voting for the different political tendencies represented during the legislative elections from 1848 to 2022. We also explain how we digitized the election records kept at the National Archives and assigned each candidate a “political nuance” (generally between 8 and 15 nuances depending on the election), based in particular on the press coverage at the time.

In order to be able to make comparisons over a long period, we also group them into “political tendencies” (Left, Center-Left, Center, Center-Right, Right) and into three main blocs: the Left bloc (Left and Center-Left), the Center bloc, and the Right bloc (Center-Right and Right).

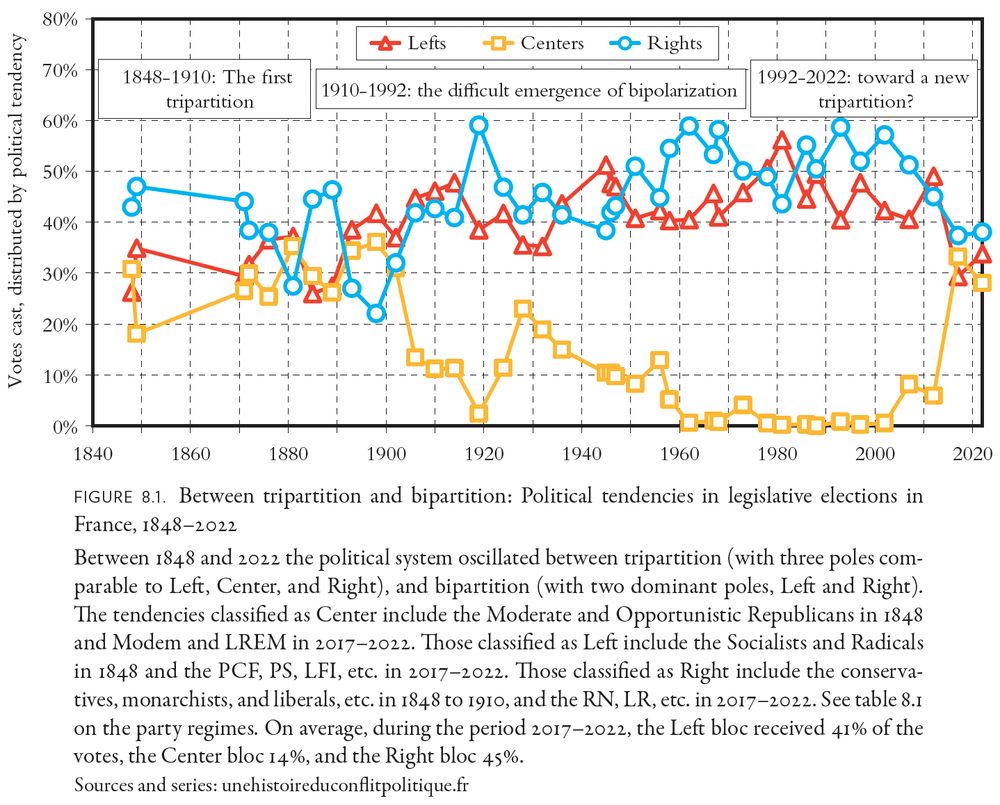

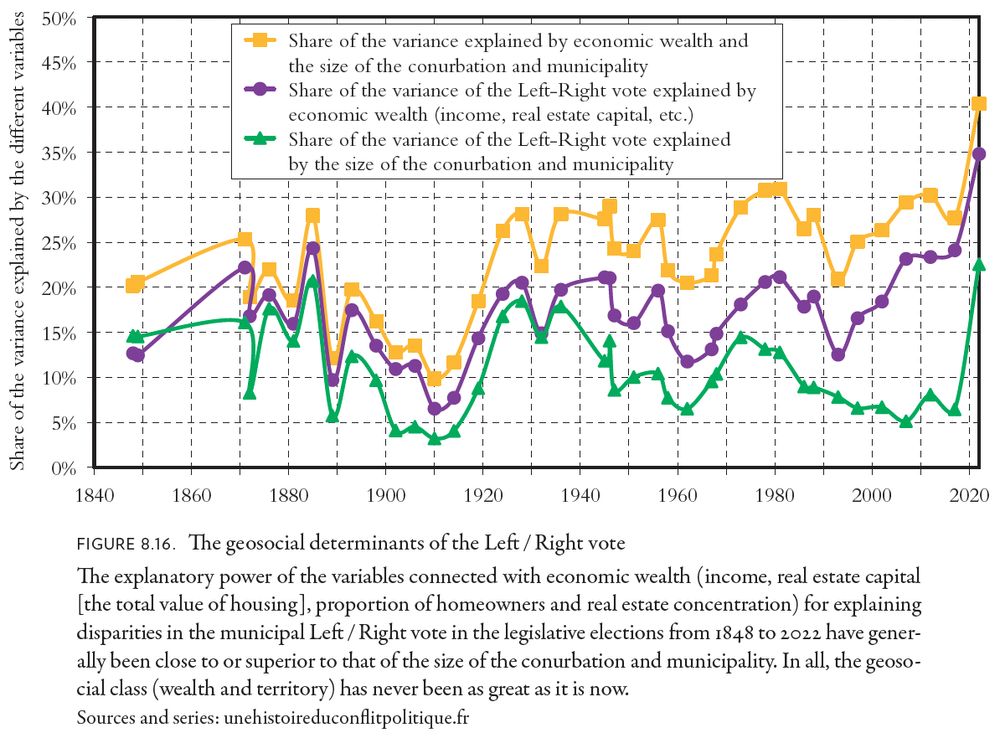

Between 1848 and 1910, the political system was characterized by a form of tripartition, with three poles of comparable size on the left (Socialists, Radical-Socialists) and center (Moderate Republicans and Opportunists) and on the right (Conservatives, Monarchists, Catholics). Then, between 1910 and 1992, the political system underwent a marked shift towards bipartisanship, with two main poles on the left and right and a center reduced to a bare minimum. The period from 1992 to 2022 seems, on the contrary, to have been characterized by a fragile return to a new form of tripartition.

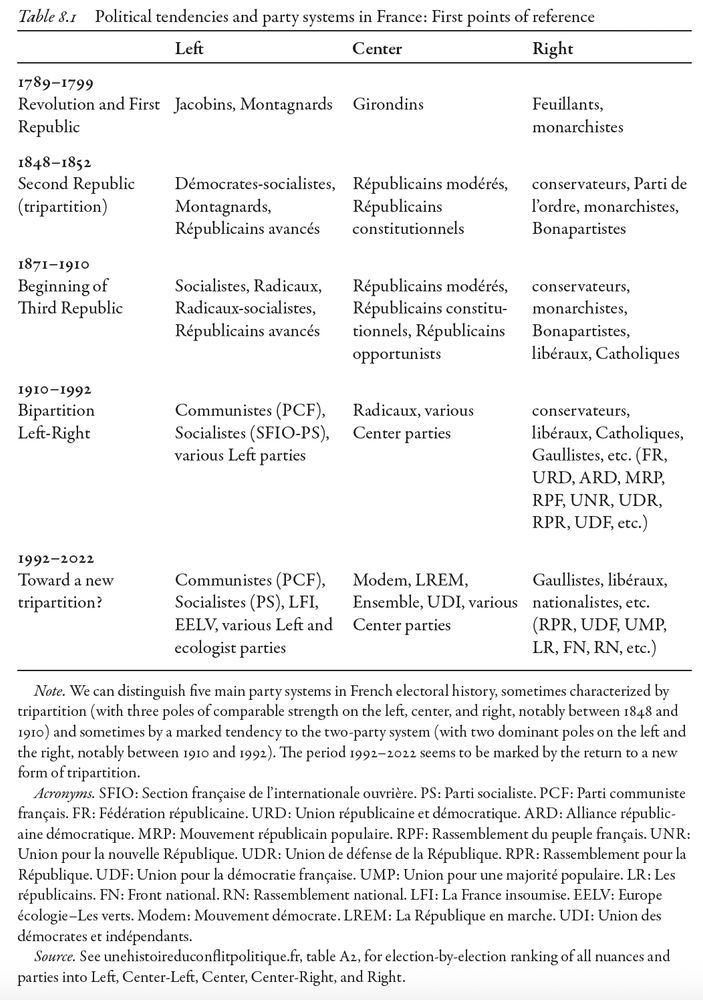

Over the long term, one of the main regularities is that the rural world has generally tended to vote more strongly to the right than the urban world. This territorial cleavage was particularly marked in the nineteenth century and again at the beginning of the twenty-first century. It tends to go hand in hand with a three-way split: the urban and rural working classes are divided between the Left and the Right, allowing a central bloc comprising the middle and upper classes to govern. Conversely, the social cleavage prevailed over the territorial cleavage for most of the twentieth century: the left-wing bloc managed to unite the urban and rural working classes and impose a left-right bipolarization.

As with turnout, we also find that the explanatory power of geosocial class in accounting for votes for the main blocs in legislative elections since 1848 has never been as strong as in the 2017 and 2022 elections. These results illustrate the structuring role of socio-economic determinants of voting over the long term (rural-urban divide, wealth divide, occupational and sectoral divide) and their primary importance compared to geographical and identity factors.

Chapter 9 - The First Tripartition, 1848–1910

This chapter studies more precisely the structure of the vote during the period 1848-1910. Despite all that separates the two historical contexts, this period seems to us particularly rich in lessons for understanding the present world, especially with its socioeconomic inequalities that are increasing in both contexts and an electoral system marked by tripartition, a system that in retrospect appears deeply fragile and unstable.

Several factors contributed to the weakening of the tripartite division between 1848 and 1910. First, the Left bloc mobilized politically to bring together the rural and urban working classes and overcome territorial antagonisms around a common redistribution program. Everything indicates that this process played an essential role in the end of the tripartite division and the transition to a left-right bipolar system, and that the same could happen in the future.

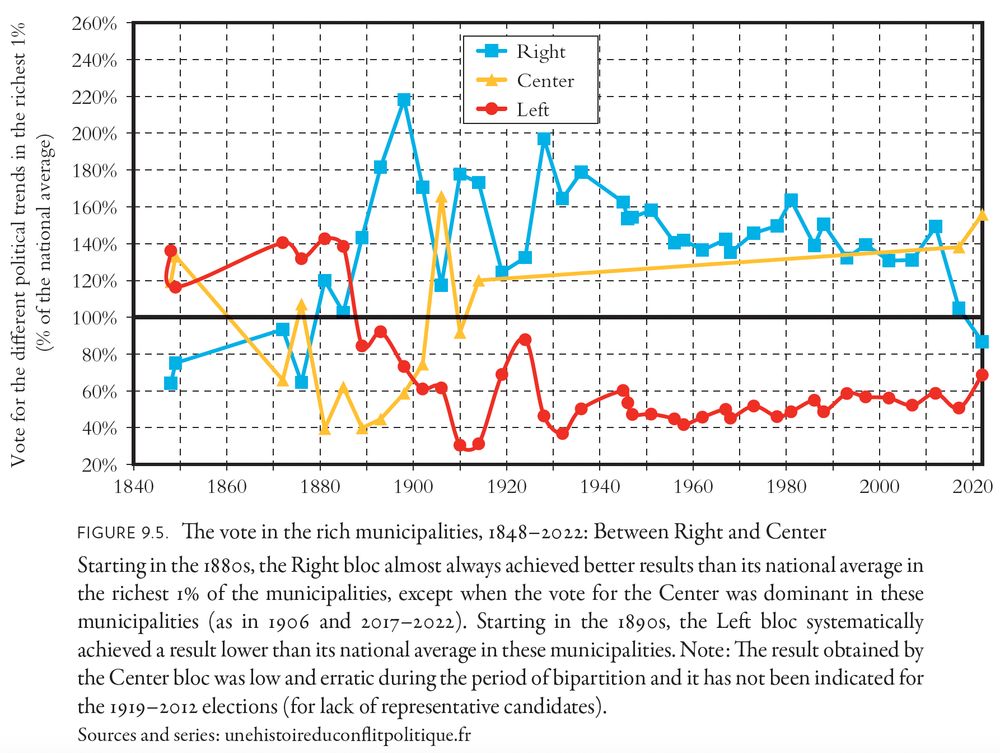

It is also important to emphasize the role played by elites, who have proven willing to move rather rapidly from the Right to the Center if it serves their fundamental socioeconomic interests. This phenomenon can be observed with the Opportunist Republicans of the 1880s and 1890s, and it is even more pronounced with the Center bloc in 2017-2022.

The complicated question is whether this plasticity and this pragmatism should be seen as an asset in political and electoral competition, or whether this “opportunism” and this supposed ability to aggregate all the elites (at the risk of being accused of social self-interest) is ultimately a weakness that contributed to the fall of the central bloc and the exit from the tripartition of the early twentieth century. We will defend the second hypothesis and the idea that such a phenomenon is already underway in the present period.

Chapter 10 - The Difficult Construction of Bipartition, 1910-1992

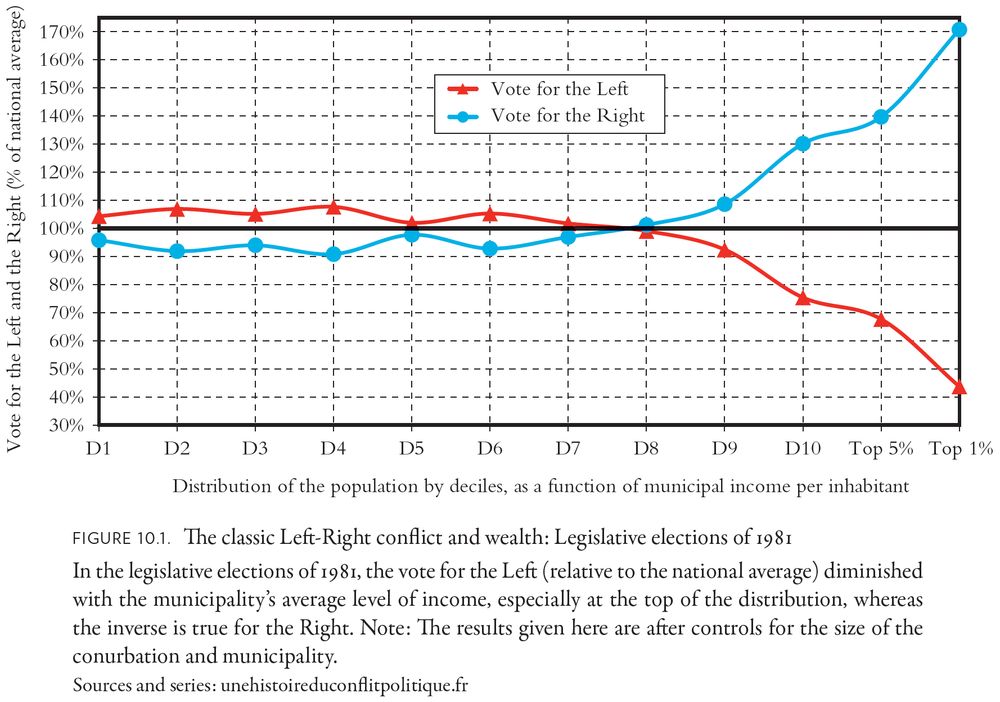

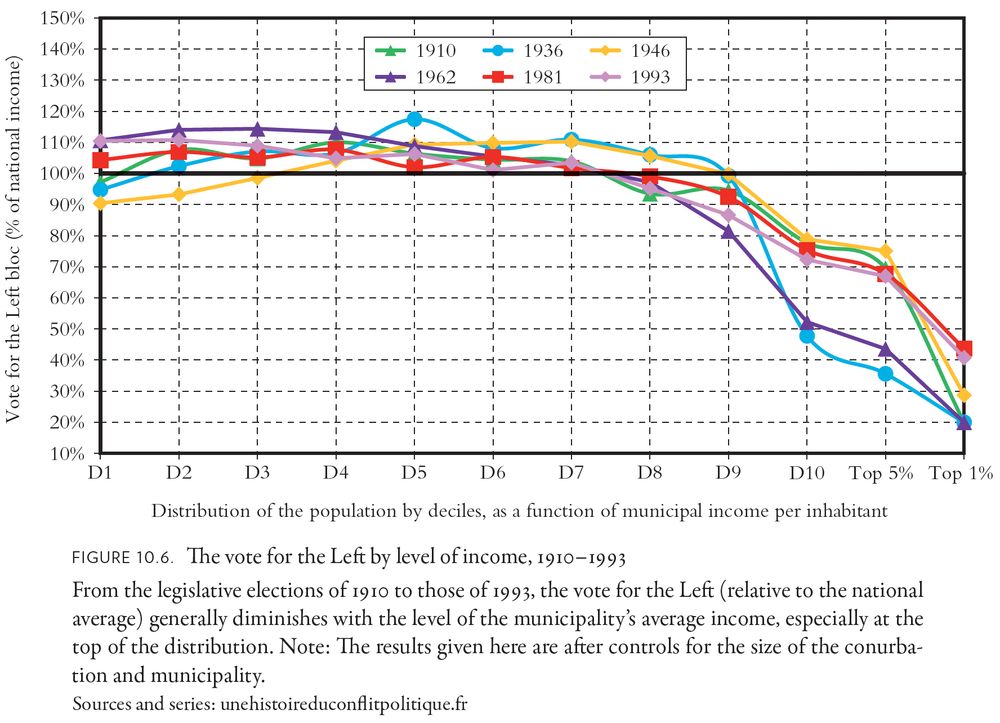

This chapter studies the structure of voting and of electoral conflict during the period 1910-1992. At first, this period seems to be characterized by a bipartition of the “classic” type, with a political confrontation centered on the social question and the redistribution of wealth. It should not be idealized, but during the twentieth century this driving dialectic did make it possible to construct an unprecedented movement (albeit insufficient and incomplete) toward greater social equality and greater economic prosperity, all in the framework of a pluralist electoral democracy based on collective deliberation, political alternation, and respect for the diversity of points of view.

For all that, the system of bipolarization that was established between 1910 and 1992 was always permeated by multiple weaknesses and contradictions that it is essential to analyze in order to better understand the system’s collapse during the period 1992–2022, as well as the conditions of its possible resurgence.

Among the many factors of the weakening of bipolarization at work between 1910 and 1992, two deserve particular attention for what we can learn from them concerning the future. First of all, in practice, the Left-Right electoral cleavage connected with wealth is always made more complex by a territorial rural-urban cleavage that partly contradicts it (the rural world being, on average, poorer and more likely to vote for the Right).

Besides, the Right bloc, like the Left bloc, is full of internal contradictions, which were especially deep during the interwar period and under the Fourth Republic, particularly in connection with the financial legacy of the wars, the inconsistencies of nationalism, the construction of the welfare state, and the question of democratic socialism. These difficulties of agreeing on a viable program often prevented clear alternations between the two blocs and regularly led to government by unstable coalitions.

Chapter 11 - Toward a New Tripartition, 1992-2022?

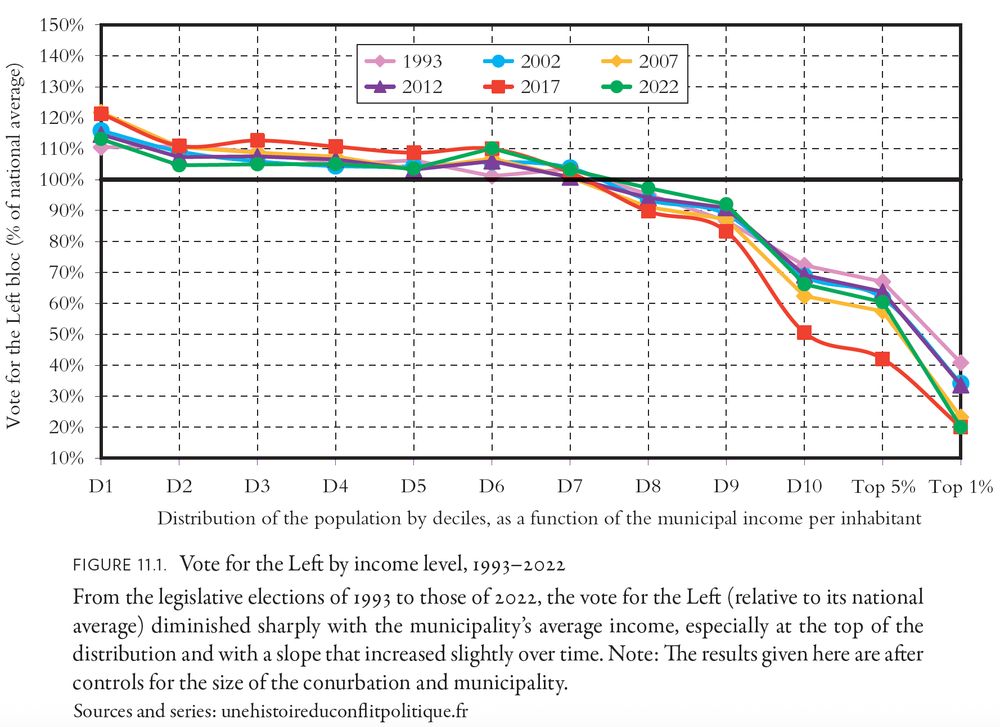

Chapter 11 analyzes the bipartition’s phase of weakening and the rise to power of a new form of tripartition that developed between 1992 and 2022.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the vote for the Left bloc has never ceased to be a strongly decreasing function of municipal wealth, even in recent decades. This is particularly true in the wealthiest municipalities, which have always voted for the Right (or the Center) and not for the Left.

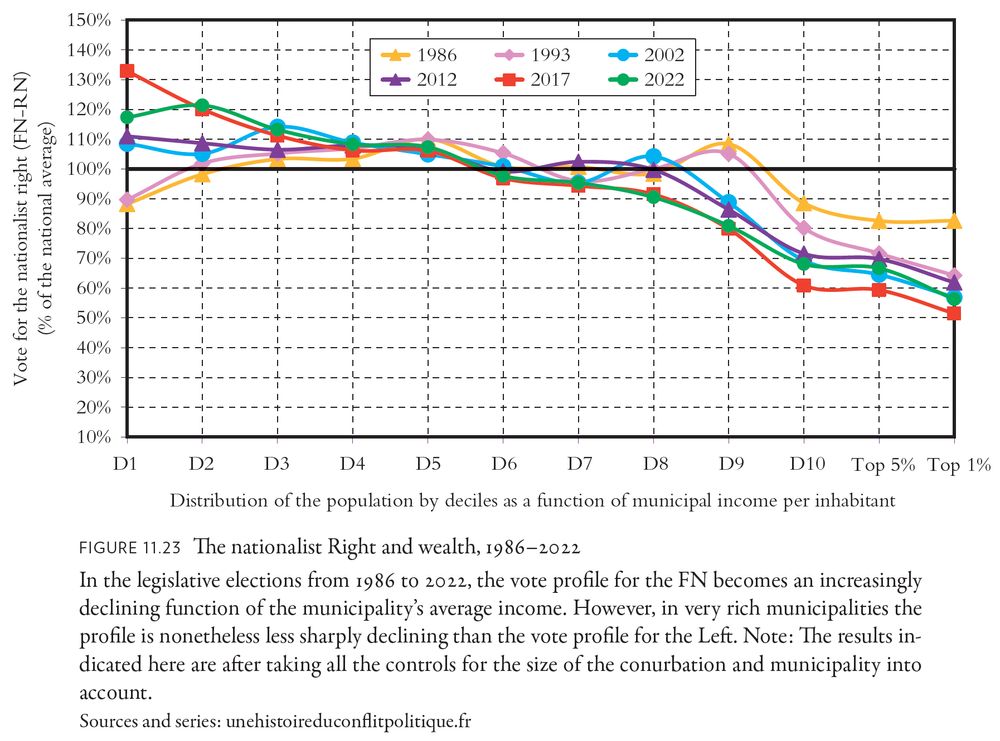

The novelty of recent decades is the emergence of another popular vote, that of voters turning to the FN-RN, mainly located in villages and towns, which since the 1980s and 1990s have attracted more industrial blue-collar workers subject to international competition than the suburbs and metropoles. The feeling of abandonment in the face of globalization, European integration, and public services has driven these voters toward the FN-RN, while service employees (commerce, catering, health, etc.) in working-class suburbs and metropoles have continued to vote for the Left.

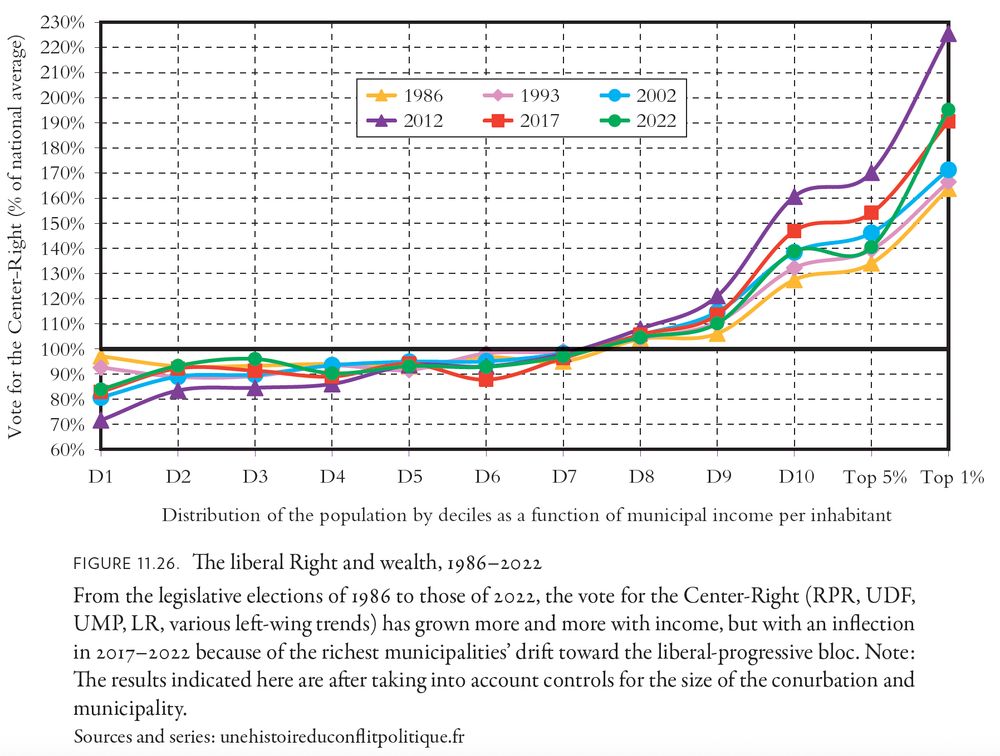

At the same time, the vote for the Liberal Right (excluding the FN-RN) has become increasingly bourgeois, partly due to the loss of the rural popular vote to the FN-RN.

Ultimately, the 2022 elections saw the emergence of a new form of social tripartition: the urban and rural working classes are divided between the Left bloc and the Right bloc, while the Center is supported by the middle and upper classes.

Chapter 12 - The Twofold Invention of the Presidential Election, 1848 and 1965-1995

The previous chapters concentrate on the structure of electorates observed in the legislative elections that have taken place in France from 1848 to 2022. This is our preferred long-term vantage point because it allows us to study both the largest number of elections and the greatest diversity of political tendencies. However, presidential elections and referenda have also played a central role in the electoral and political dynamism of the country over the course of the last two centuries, and particularly in the recent period.

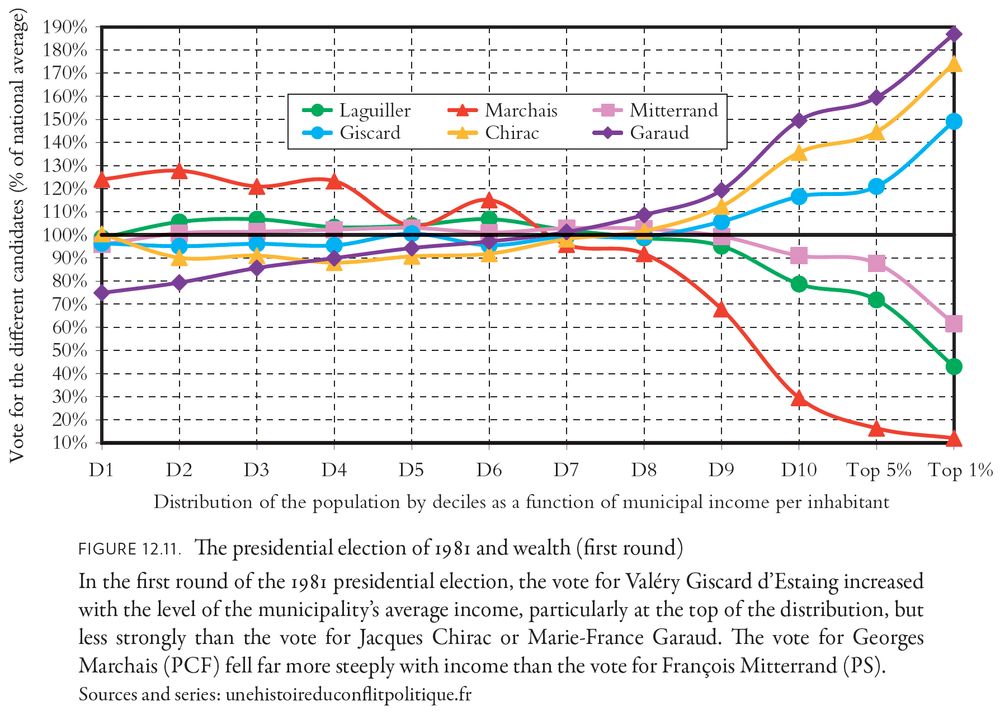

While the 1848 presidential election was disastrous, the reintroduction in 1965 of the presidential election by universal suffrage helped to strengthen the Left-Right bipolarization centered on the social question and the problematic redistribution of wealth, like the symbolic election of 1981.

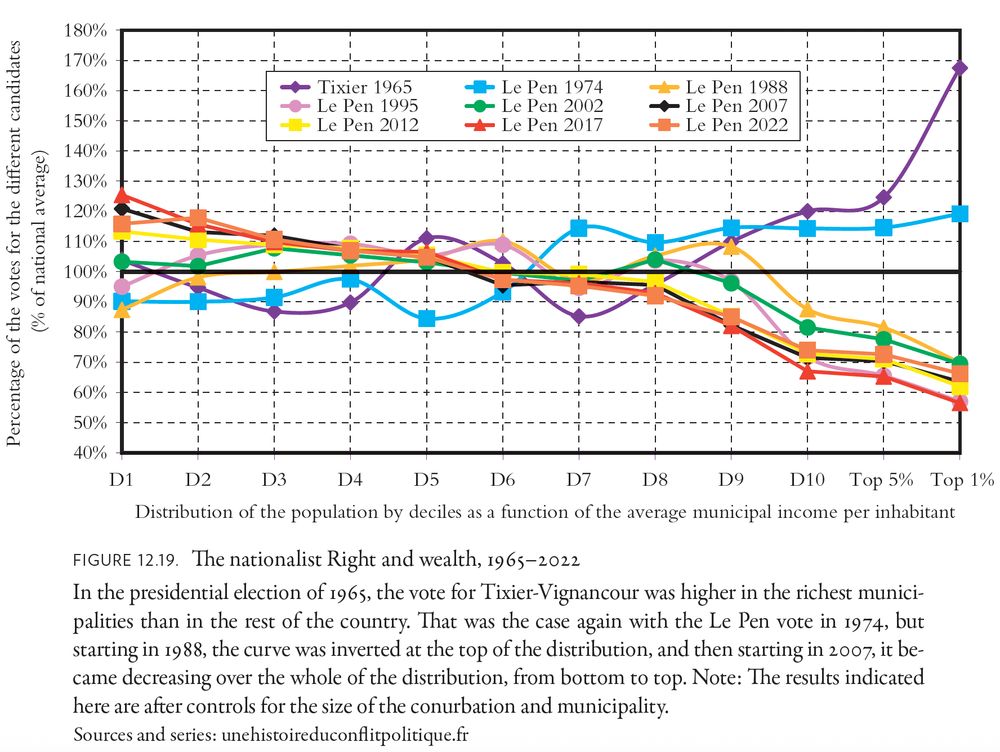

The presidential election also contributed to the emergence of new political tendencies, particularly the vote for the national Right, which was urban and affluent in 1965 and 1974 and has become increasingly rural and working class since the 1990s and 2000s, as the FN-RN has attracted voters disillusioned with globalization and European and international trade integration.

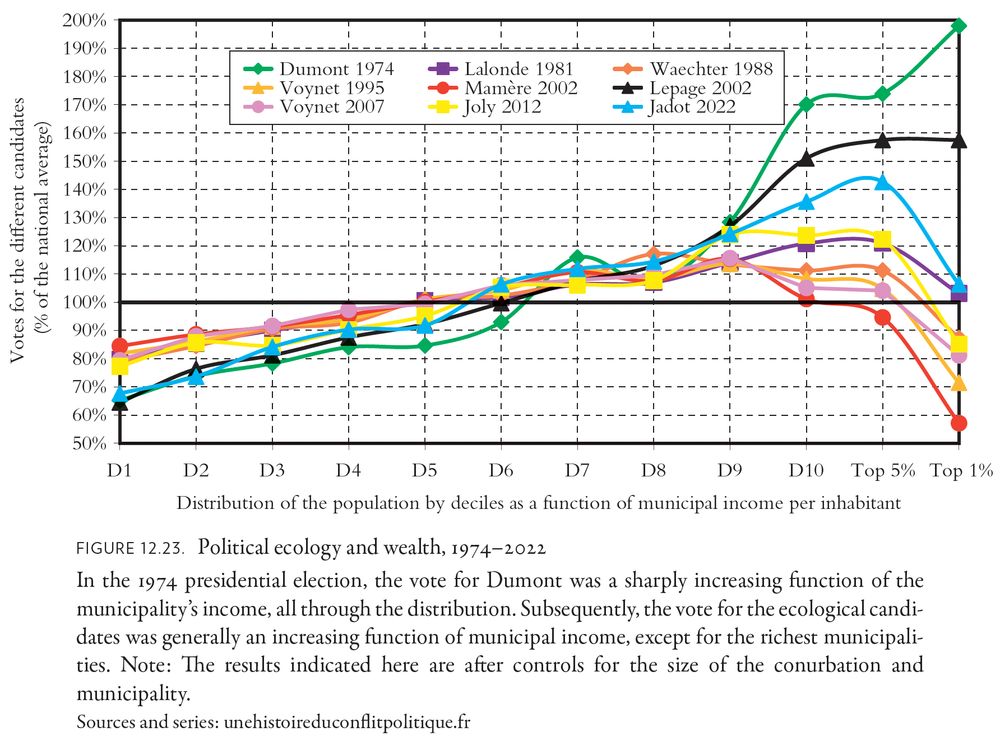

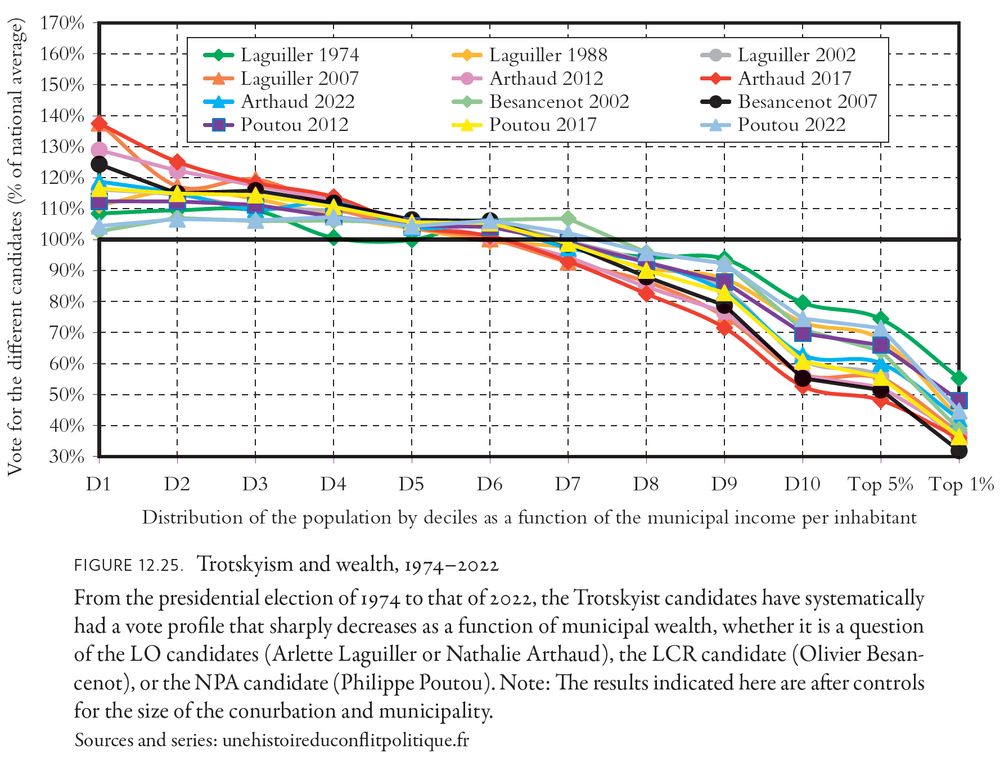

The study of presidential elections also highlights extremely differentiated voting patterns within other political families, with, for example, a relatively urban and affluent vote (even within conurbations and municipalities of the same size) in favor of political ecology since 1974, and, conversely, a rural and working-class vote for Trotskyist candidates.

Chapter 13 - The Metamorphoses of the Presidential Election, 2002-2022

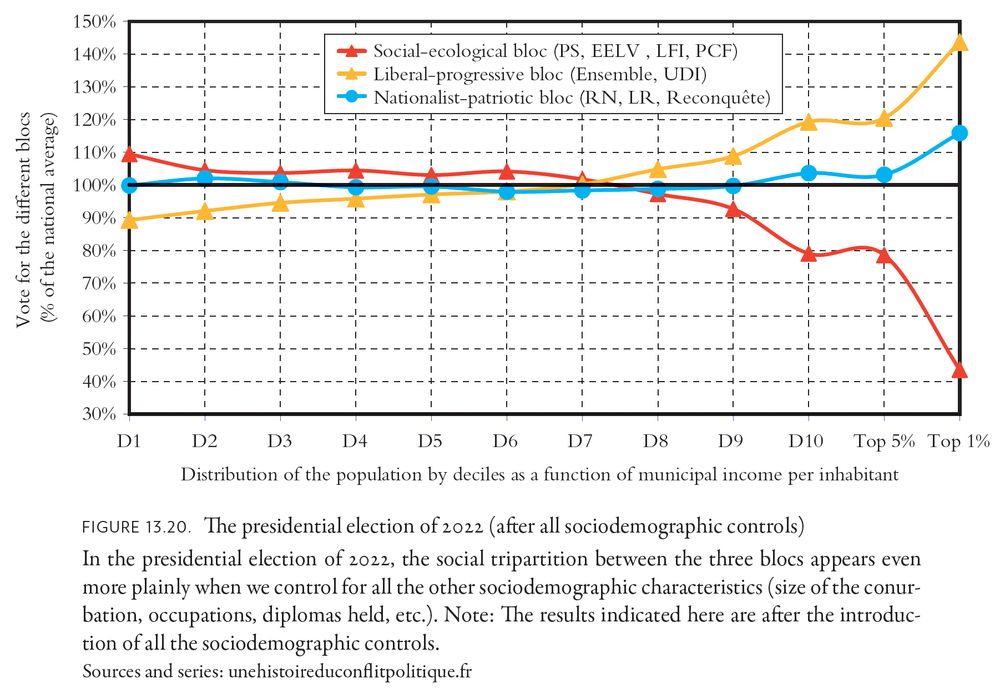

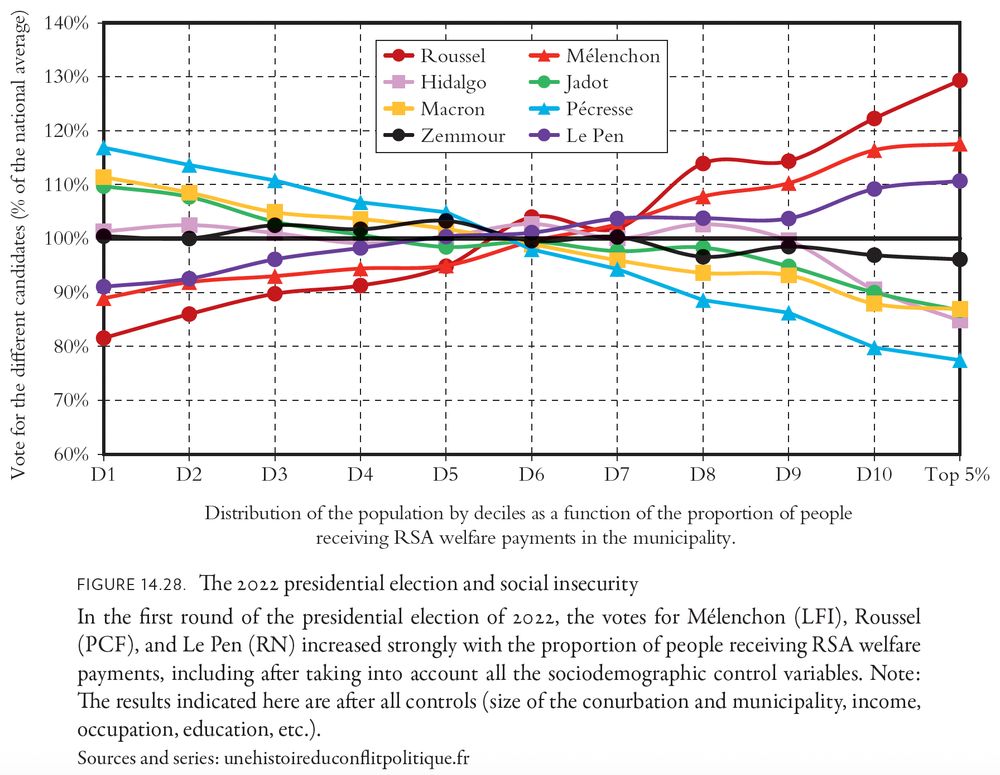

As with the legislative elections, the 2022 presidential election saw the emergence of a new social tripartite division, with the urban and rural working classes divided between the Left bloc and the Right bloc, and the middle and upper classes supporting the center. If all other things are equal, i.e. if controls are introduced for other socio-demographic characteristics (size of conurbation and municipality, occupation, educational qualifications, etc.), we nevertheless see that the vote for the Left bloc continues to decline sharply with wealth, while the vote for the Right bloc remains virtually flat (or even slightly increases). This can be explained by the fact that the RN vote only decreases slightly with wealth (all other things being equal), while the Reconquête-LR vote increases very sharply with wealth.

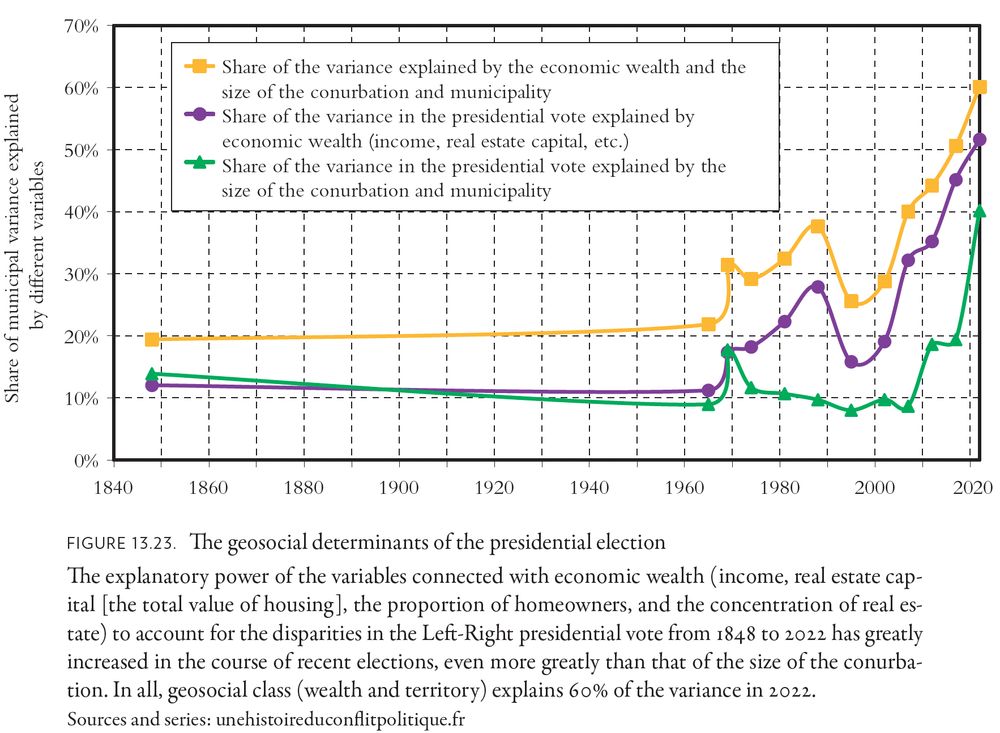

We also observe that the explanatory power of geosocial class in accounting for the vote for the main blocs has never been as high as in the last presidential elections. These results once again illustrate the structuring role of socio-economic determinants of voting over the long term (in particular the economic wealth of the municipality and the size of the conurbation and municipality) and their primary importance compared to geographical and identity factors (especially compared to the proportion of people of foreign origin, which explains only a very small part of the voting differences).

Chapter 14 - The Role of Cleavages in Referenda and the European Question

Cleavages in referenda have played an important role in structuring political conflict for two centuries, particularly during the founding referenda of 1793 and 1795, as well as during the constitutional referendum of 1946 on the abolition of the senatorial veto, which was characterized by a particularly marked left-right cleavage around wealth.

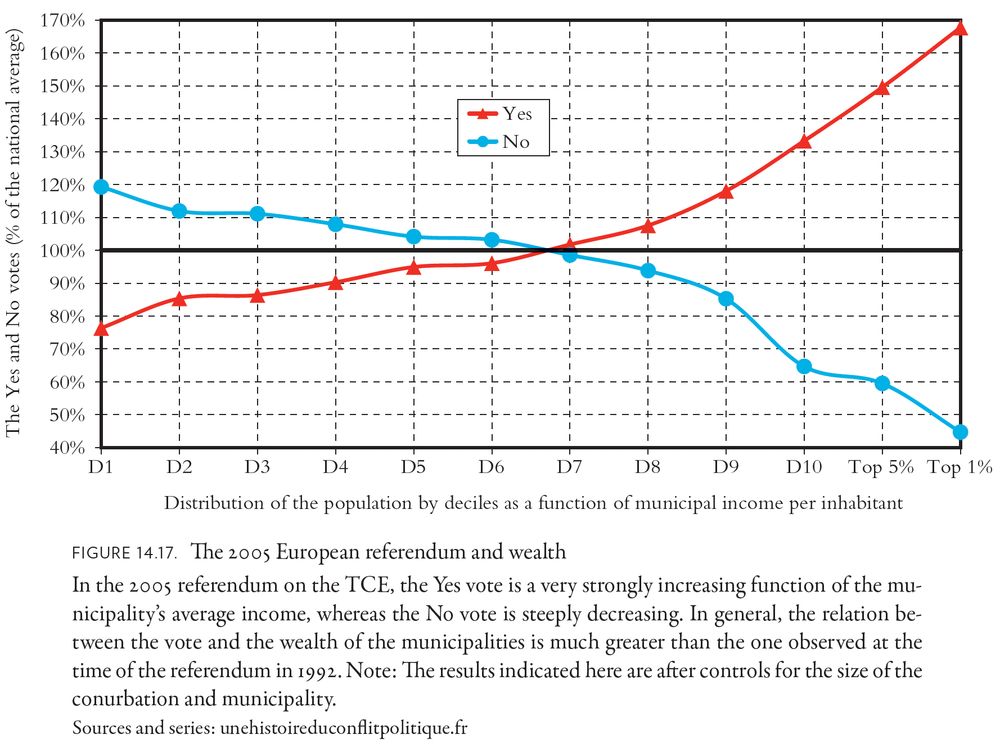

The European referenda of 1992 (Maastricht Treaty) and 2005 (European Constitutional Treaty) were also key political moments. They played a central role in the process leading to the weakening of the Left-Right cleavage and the rise of tripartition, with a central bloc supporting liberal Europe and two lateral blocs opposing it on different and largely irreconcilable grounds. In fact, the Yes vote in the 2005 referendum was a very strongly increasing function of wealth: it brought together the middle and upper classes from the Left and Right who were generally satisfied with globalization and their economic situation. Conversely, the No vote declined sharply with wealth. It was highest in working-class urban and rural communities, which subsequently voted increasingly separately, the former for the Left bloc and the latter for the Right bloc, while the new Center bloc drew support from the middle and upper-middle classes.

Information from individual surveys confirms the conclusions drawn from municipal election data, particularly with regard to the division of the urban and rural working classes between the Left and Right blocs. Among the 50% of voters with the lowest incomes, the Left bloc achieved its best results among urban service employees (commerce, catering, health, etc.) and the most precarious voters (when they vote), while the Right bloc achieved its best results among blue-collar workers and the middle classes in towns and villages most exposed to international competition.

Conclusion

In this book, we have attempted to write a history of political conflict that is based on the French laboratory. France is a country that has had a rich and eventful political and electoral life from 1789 to 2022 and thus offers a particularly relevant vantage point from which to observe the hopes of the democratic idea and the complex paths it has taken over the last two centuries.

Perhaps the most important finding of our research is that social class has never been as important for understanding voting behavior as it is today. In our view, this is an optimistic conclusion, in the sense that political and electoral conflicts are decipherable and can be resolved through socioeconomic means. In other words, we reject the notion that present-day political conflicts have become unreadable, dominated by democratic exhaustion, identity and community clashes, or the reign of post-truth. Political conflict does not pit the camp of reason against that of folly. Today, as yesterday, it opposes contradictory socioeconomic interests and aspirations. It can be overcome only through democratic alternations in power and further transformation of the socioeconomic system, a process that has already been underway for the past two centuries and will not end today - whatever the conservatives of any era may think.

The pursuit of this transformation nonetheless requires a long political and programmatic process that aims to reconcile the interests and aspirations of urban and rural worlds and allow the social divide to prevail over the territorial divide. It was this process that enabled the rise of the Left-Right bipolarization at the beginning of the twentieth century. A similar process now appears necessary in this early part of the twenty-first century, above all taking into account the increasing complexity of class structure, which is characteristic of an advanced welfare state grappling with unbridled international competition.